Lady Gaga should play Rose in Streisand's "Gypsy"

Arguably, few movie remakes are as good as the originals and, as a general rule, the average film buff is contemptuous of remakes. But that hasn't stopped any self-respecting buff from indulging in fantasy casting.

Count me in.

Which brings me to "Gypsy" and Barbra Streisand's crusade to film another version, reportedly based on a new script by the estimable Richard LaGravenese ("The Fisher King," "Beloved" and "The Ref").

As regular readers of this site know by now, "Gypsy" remains my favorite musical - I saw the original production as a kid, my first stage show ever (I'm seriously dating myself here) - as well as my favorite movie musical.

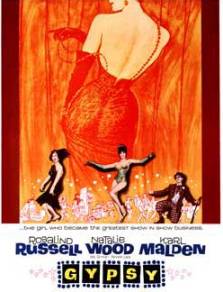

Mervyn LeRoy's 1962 film version, with Rosalind Russell's definitive reading of the role of Rose Hovick, is letter-perfect, even with the few ill-advised cuts that LeRoy made following its first previews.

An unnecessary and unmemorable 1993 TV movie, directed by Emile Ardolino and starring a seemingly well-cast but surprisingly ineffectual Bette Midler, succeeded only in making the LeRoy film look even better.

Much better.

Streisand's plan is to direct the new version and play the role of Rose.

The idea of Streisand singing the "Gypsy" score is irresistible. She would have made the perfect Rose - would have. Streisand will be 74 in April and may well be a few years older if Universal decides to back the film.

"Gypsy" spans about 10 years, opening with Rose as the mother of two little girls who, I'm guessing, are about seven and eight. It ends with the still-young title character becoming a phenomenon in burlesque.

Rose should be 30 at most when the show opens and about 40 when she triumphantly/pathetically sings the searingly biographical "Rose's Turn."

Forty years ago, Streisand undoubtedly would have been a revelation as Rose and apparently LaGravenese thinks she is still right for the role.

Recently, Streisand has aligned herself with Lady Gaga and expressed interest in casting her in "Gypsy." Great, I thought. Barbra is going to direct Gaga (né Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta) as Rose.

Gaga is 29 and would be a terrific Rose, considering (1) her age, (2) her demeanor and (3) her vocal range. But I assumed wrong. Streisand's idea is for Gaga to play Gypsy to Streisand's Rose.

None of this is exactly new. Over the past 50-plus years, there have been only a handful of productions of "Gypsy" and, by extension, a handful of actresses playing Rose, the crown jewel of musical comedy. But all of them have been examples of ageist casting (yes, ageist, but not in the direction you think). Why has the character of Rose traditionally been cast with an actress well into her 50s (at least)? Imagine how different - and revelatory - it could be with a younger, vibrant performer in the role.

But this has never happened.

Wait. It happened once. No, twice. In 2004, Andrea McArdle, then 40, played Rose in The Bay Area Houston Ballet and Theatre production of "Gypsy." At 40, McArdle (who has the perfect voice for the role) was a decidedly youthful Rose. It probably also helped that McArdle invariably identified with the material, having started out as a child actress (read: "Annie"). Mary McCarty, who replaced Ethel Merman in the Broadway production in 1961, was 38 at the time. (McCarty played Mother Goose in Disney's "Babes in Toyland," which co-starred Ann Jillian as Bo Peep; Jillian would play Dainty June in the '62 film version of "Gypsy.")

And, in 1964, songstress Gisele MacKenzie played the part in Berkeley at Ben Kaplan's Meadowland Theater. She was - ta-da! - 37.

MacKenzie is the youngest Rose Hovick to date.

The oldest Rose? That would be Leslie Uggams who was 71 when she played Rose in the 2014 production at the Connecticut Repertory Theater. Wow! She is followed, but not too closely by Patti Lupone who was 60 when she undertook the part in the most recent - 2008 - Broadway revival of the show. The talented Lupone was 58 when she also played the role in the 2007 Encores! production and 57 when she tackled it for the first time for the 2006 Ravinia Festival production.

Following Uggams and Lupone, age-wise, are these top-notch actresses, some miscast, some well-cast, but all a tad too old for the role, a trend that I covered in an earlier essay here:

Imelda Stauton, age 59, pictured below (2015 British revival at London's Savoy Theater; see Michael O'Sullivan's coverage here from his excellent site, Mike’s Movie Projector)

Ann Sothern, age 58 (1967 touring Music Fair production)

Ethel Merman, age 57 (original 1959 Broadway production)

Patty Duke, age 57 (2003 Spokane, Washington Civic Theatre production; Duke below with co-stars Danae M. Lowman and Reed McColm)

Bernadette Peters, age 55 (2003 Sam Mendes revival)

Rosalind Russell, age 55 (original 1962 film version)

Tovah Feldshuh, age 55 (2008 Bristol Riverside Theater production)

Linda Lavin, age 52 (succeeded Tyne Daly, below, in the 1989 revival)

Betty Buckley, age 51 (1998 Papermill Playhouse production; Debbie Gibson co-starred as Louise/Gypsy)

Joanne Worley, age 51 (1988 The Civic Light Opera of San Gabriel Valley; Audrey Landers co-starred as Louise/Gypsy)

Angela Lansbury, age 49 (1973 London production, followed immediately by the first Broadway revival in '74)

Bette Midler, age 48 (1993 TV-movie remake)

Vicki Lewis, age 48 (2008 California Musical Theater production)

Betty Buckley, age 45 (1992 Southern Arizona Light Opera Company production)

Tyne Daly, age 43 (1989 Broadway revival)

Betty Hutton, age 41 (1961 National Tour)

But somehow, the role has evaded such powerhouses as Carol Burnett, Liza Minnelli and ...Streisand! And Stockard Channing would have been an absolutely terrific, atypical choice for the part but a natural.

But back to "a younger, vibrant performer in the role." Well, that would be Gaga, hands-down, who could be easily aged for the later scenes. ("Youthening" someone - is that a word? - is much more difficult and rarely convincing.) Plus - and this is probably important to Universal - Gaga would bring bodies into the local multiplexes to watch her in action.

While we're at it, let's cast the other roles, all within the right age range. (It's called fantasy casting, see?)

Herbie: Adam Levine (he would match up well with Gaga, his personality would fit the part and, of course, he can sing)

Louise/Gypsy: Jennifer Lawrence (she could be a-mazing.)

Tulsa: Zac Efron

Dainty June: Elle Fanning

Miss Cratchet: Allison Janney

Tessie Tura: Tina Fey

Electra: Amy Poehler

Miss Mazeppa: Amy Schumer

Baby June: Alyvia Alyn Lind

Baby Louise: Sophie Pollono

That said, wishing Barbra the best of luck with her dream project.

Below: Audrey Landers (left) and Joanne Worley (center) in The Civic Light Opera of San Gabriel Valley production