Howard

Zieff (1927-2009) emerged as a filmmaker of some promise in 1973, just

as the exciting New Wave in American filmmaking was hitting its peak, an exciting movement that started in the late 1960s with such titles as "Bonnie and Clyde," "Medium Cool," "The Graduate," "Midnight Cowboy" and "Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice."

Consequently,

he became something of a footnote to the movement, unjustly forgotten

when critics rhapsodize about the movies of the late 1960s and early

'70s.

One could speculate, I guess, that the neglect

he experienced had something to do with his age. He was 46 when he

made his first film in 1973 - the new-style caper-comedy, "Slither" -

while Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were all in their late 20s

when they officially advanced the movement with such films as "The Rain People" (1969), "The Sugarland Express"

(1974) and "American Graffiti" (1973). Of course, all three would inevitably abandon the cutting-edge of the New Wave for the glories (and financial security) of

studio blockbusters.

And I should hasten to note

that Zieff wasn't the only middle-ager making movies directed at the youth market. Robert Altman (age 45), Arthur Penn (also 45), Hal Ashby (41) and Paul

Mazursky (39) are just three Zieff peers who were no longer ambitious puppies of the movie business when they each hit it big (at the ages given here), making vital films.

It's

more likely that Zieff's

history was problematic with the influence

peddlers. He made his feature debut after an incredibly successful

career in advertising, specifically making memorable TV commercials for

such products as Alka-Seltzer and Hertz. But it was exactly the

elements that he learned from making commercials - a feeling for speed,

brevity and short-hand - that make his handful of movies so

exhilarating.

Case

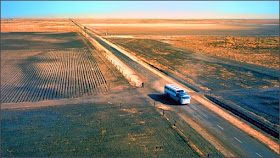

in point: "Slither," a scattered, free-form lark that plays like a

Godard film shot in the most unlikely California locations. (Anyone

game for visiting Susanville?) James Caan and Sally Kellerman as Dick

Kanipsia and Kitty Kopetzky, reluctant traveling companions, are like a

weirdly zoned-out Bogart and Bacall, and they keep bumping into an

assortment of eccentric characters, gamely played by Peter Boyle, Louise

Lasser, Alex Rocco, Allen Garfield and Richard B. Shull.

It always amazed me that Zieff managed to make a film as shaggy and as studio-unfriendly as "Slither" for James Aubrey during his tumulative reign at MGM.

Zieff made only nine films over a 20 year period and each one is a gem of comic economy.

The title that followed "Slither" two years later is, arguably, his

smoothest and most refined - "Hearts of the West," which played the 1975

New York Film Festival and became an instant critics' darling. It appealed to obsessed cinéphiles, too. A love

letter to early filmmaking, "Hearts of the West" is something of a

companion piece to Peter Bogdanovich's "Nickelodeon," which curiously

came a year later.

Jeff

Bridges plays the hayseed author of dime novels about the old west

who finds himself a reluctant star of movies about the old west ("reluctant" seems to be a word that fits Zieff films and characters)

and the actor inhabits the role completely - as does Andy Griffith as

his (reluctant) mentor. Blythe Danner is the winsome female lead and

there's nice work here by Alan Arkin, Herb Edelman and, from"Slither,"

Rocco and Shull.

Following "House Calls" (1978), a

mature rom-com with Glenda Jackson and Walter Matthau (with a script to

which Max Shulman and Julius J. Epstein, no less, contributed), and "The

Main Event" (1979) which offered a terrifically appealing reteaming of

Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal, Zieff enjoyed his biggest commercial

hit in 1980 - the inspired feminist romp, "Private Benjamin," with

Goldie Hawn in her most emblematic film performance as a Jewish American

Princess who is swayed by disreputable recruiter Harry Dean Stanton

(yes!) to join the United States Army.

Hawn is delirious

fun as the clueless Judy Benjamin who does her Army maneuvers with limp

wrists and no coordination whatsoever and who, with a straight face,

asks her drill sergeant (a perfect Eileen Brennan) exactly where are all

the beach condos that Stanton promised in his pitch.

Zieff

was absent for about four years before he did his 1984 remake of the

1948 Rex Harrison film, "Unfaithfully Yours," with Dudley Moore in the

reimagined Harrison role and Nastassja Kinski filling in for Linda

Darnell. And then came the Michael Keaton comedy in 1989, "The Dream

Team," the least of all his films. But the endearing "My Girl" (1991)

came next.

A winning film about coming of age - in this case, a rare one about the coming of age of a

girl

- "My Girl" is a warm but also alert and rather eccentric look at family and

friends and the passing of time and ... life. Thanks to Zieff's adroit

touch, the film is as comfortable as an all-embracing, overstuffed

chair (with an ottoman, natch) - and that's probably the exact kind of

place you'd want to sit while watching it.

The movie introduced the remarkable Anna

Chlumsky, a little girl with a huge face, as the young heroine, a

motherless kid named Vada who lives in a funeral parlor with her father

(Dan Aykroyd) and uncle (Richard Mazur) and who finds a fleeting

soulmate in Macauley Culkin and a soul sister in the beautician (Jamie

Lee Curtis) hired to make the corpses look, well, lifelike. His last film was the unnecessary '94 sequel, "My

Girl 2."

The crucial eccentricity (by now a Zieff trademark) of "My Girl" is underlined by Chlumsky's unusual name, Vada, and also by the film's original (and more

singular) moniker, "Born Jaundiced," a title which Vada explains in a voiceover.

The film's producer Brian Grazer reportedly came up with the banal "My

Girl" (with its convenient music tie-in) and I've a hunch that the change was

made much to its director's chagrin. I mean, how could Howard Zieff, of all people, not prefer "Born

Jaundiced"?

Zieff was 67 when he decided to retire. He died,

at age 82, some 15 years later in 2009 - of Parkinson's disease - and his vision is much missed.